Tottenham Court Road is full of London’s iconic red double-decker buses. These buses are very modern now – very different from the old buses that frequented London’s inner roads in the 1950’s. As I pass them, I look to see if they have the spiral stairs that take passengers up to the top deck and then I wonder if there are female bus conductors trotting up and down the stairs all day long.

I hope that there are female bus conductors – women who have healthy knee joints that enable them to climb up and down the stairs. Because if there are, then every time they go up and down those stairs, they are helping their heart health.

Over 50 years ago, the London bus conductors study paved the way for our improved understanding of the link between physical activity and prevention of heart disease. Professor Jerry Morris published his studies in the Lancet medical journal showing that London bus conductors, who had spent their working lives walking up and down the steps of double-decker buses had lower levels of coronary heart disease compared to the drivers of the same buses. The drivers sat all day, the conductors moved. It was the same for London postmen, who spent their days walking to deliver letters when compared to studies of more sedentary clerks and telephonists working in the postal offices at the time.

These studies conducted over 50 years ago have paved the way for an incredible body of knowledge on the links between physical activity and fitness and cardiovascular disease, which comprises heart disease and blood vessel disease such as strokes. The only down-side has been that many of these early studies were conducted on men and not women.

As I wander along Tottenham Court Road today, ducking the never-ending stream of shoppers, I’m thinking about this early research. These studies led to the phenomenal growth in exercise science research that has continued unabated since the late 1980’s. Two approaches to measuring cardiovascular fitness evolved from the seminal London bus conductors studies. One approach has been for researchers to use questionnaires to evaluate physical activity levels whilst the other approach has been to use objective fitness tests to measure cardio-respiratory fitness – did you ever wonder why that despised ‘Beep Test’ originated in schools? What’s better known now though, is that heritable factors are now estimated to contribute between 10-50% of the variance in fitness.

I’m going to talk about heart disease and cardiovascular fitness in my Masterclass on Menopause seminars in the United Kingdom. But I’m not going to talk about the London bus conductors’ study. You see, this was done on men, not women – and certainly not menopausal women. Yet it’s important research, because it has opened the door to better understanding about the role physical activity plays in women’s cardiovascular health as we age. Cardiovascular disease is the number one health concern for women living in western societies as they move into post-menopause, especially if they are overweight or obese. Prevention during our vulnerable years in menopause is crucial and it’s this that I continue to share with women at my seminars and in the MyMT programmes.

The concept that a high level of physical activity and/ or fitness might offer protection from the adverse cardiovascular consequences of obesity has gained considerable momentum over the past 4 decades. However, from the London bus conductors study in the 1950’s to the investigation of San Francisco Longshoremen (dockworkers), by Ralph Paffenburger in the 1970’s, to the famous Whitehall Study which looked at the cardiovascular fitness levels of over 9,000 English male civil servants and their risk for heart disease, there have been numerous gaps in research about women’s cardiovascular health and their physical activity levels.

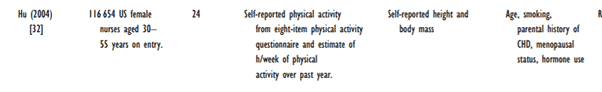

In fact, it wasn’t until 2004, that women really got a look-in. In the United States, one of the largest studies (over 100,000) was conducted on nurses. Thank you to those nurses and the researchers, because this was the start of improved understanding about how much physical activity is needed for us to stay healthy. What was noted in this study as well, were that several risk factors in women increased their risk for cardiovascular disease. Smoking had the highest risk, but so too did family history of heart disease, menopausal status and hormone use (although the hormone-use concerns have been better scrutinised in further work since and the jury is still out on this).

Taken together, the weight of evidence from epidemiological studies of physical activity or fitness and body fatness over the past 50 years, indicates that a physically active lifestyle and/or a moderately high level of fitness (i.e. not in the bottom 20% of the population) reduces the risk of Cardiovascular disease and Coronary heart disease, especially in the overweight and obese. There is a dose–response relationship between physical activity and health which is the equivalent of expending approx. 200 kcal/day (where 1 kcal ≡ 4.184 kJ) in meaningful activity. Walking briskly for 3.2 km would meet this target.

How physical activity helps reduce our risk of cardiovascular disease is also just being better understood. It is increasingly known that inflammation plays a central role in the progression of cardiovascular disease, whereby there is plaque formation in arteries. I talk about inflammation a lot in my seminars, because as women in our 50’s we are the first generation to have been subjected to so many influences on changing inflammation in the body. From processed foods, to chemicals to too much exercise, we often hold pockets of inflammation in and around our liver, gut, blood vessels and muscles, which also includes cardiac muscles. As well, I remind women that menopause itself is the biological gateway to our ageing, and as Professor Garry Egger said at a recent conference I attended, “Ageing itself is inflammatory.”

But for those of you who are too tired, too busy or menopause hormonal changes have left your muscles and joints sore, exercise can be difficult to not only do, but to fit into your day. Even I used to find this as well – and for someone who has had a lifetime of being active, this was a bitter pill to swallow. But when we allow the right amount and type of physical activity back into our lives, we are also reducing inflammation in a body that has been accumulating inflammation for decades.

Current United Kingdom, Australian, New Zealand and United States physical activity for heath guidelines are that all adults should ‘accumulate 30 min or more of moderate-intensity physical activity on most, preferably all, days of the week’.

But is this really enough to mitigate cardiovascular risk as we move into post-menopause? Possibly not, say researchers, but I say, “It’s a start, so aim for this at least.” 30 minutes of moderate physical activity/day is likely to be insufficient for the maintenance of a healthy body weight in many individuals and the optimal physical activity ‘dose’ for obesity prevention is still unclear, but in some studies, it is suggested that as much as 60–90 minutes of moderate activity/day in groups susceptible to weight gain is required. Finding time for this is tough for women who have so much going on in their lives. Especially when you live in a big city such as London. But if you can find pockets of time during your day to be active and also climb stairs briskly and walk briskly in your lunch-break then this is a great start. Perhaps you can do more in your weekends when you do have time.

The research on women’s healthy ageing is the research I try to follow as much as possible. Much of this is research that has been centred around Blue Zones countries – regions around the world whereby women are living functional and healthy lives, free of the heart disease and cardiovascular problems that beset millions of women living in Western societies.

This is some of what I will be talking about in my seminars in the UK. Because if we can be inspired by the fact that women in Blue Zones countries move all day long and remain active and strong through their daily physical activity and live purposeful lives to a ripe old age, then this gives us a wonderful template for our future post-menopause years. This is the research that matters to women’s health as they age.

References:

Daskalopouloua, C., Stubbs, B. et al (2017). Physical activity and healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 38, 6–17.

Egger, G. & Dixon, J. (2014). Beyond Obesity and Lifestyle: A Review of 21st Century Chronic Disease Determinants. BioMed Research International Volume, Article ID 731685, 1-12.

Gill, J. & Malkova, D. (2006). Physical activity, fitness and cardiovascular disease risk in adults: interactions with insulin resistance and obesity. Clinical Science,110, 409–425.