Self-identity is a curious thing. I thought about it when I was sitting in Row 3 on the flight from Canberra to Sydney last Friday sipping on my coffee with the Sydney Morning Herald open on the political pages reading about Australia’s upcoming election. But it wasn’t the political debates I was reading, it was an article blaring the headline, ‘Natalie Joyce turns nightmare into triumph.’ [Sydney Morning Herald, April 4th, 2019].

I don’t know Natalie Joyce, but the image of her in a bikini in a body-building competition on the political pages of the Sydney Morning Herald, suggested that her personal ‘triumph’ was attributed to attaining what the young journalist heralded as, ‘the revenge body’. As I read on, I caught up with what most Australians probably know already and that is the emotional crisis she was under when her high-profile politician husband left her and their four daughters to take up with his very pregnant personal secretary. In the words of Ms Joyce at the time, “The situation is devastating on so many fronts. For my girls … and for me, as a wife of 24 years, who placed my own career on hold to support Barnaby throughout his political life.” The article then goes on to explain that, in rediscovering her own identity, she headed to the gym. The remarkable result after only a year was a body-fat percentage that the rest of us can only imagine and a 4th place in her first body-building competition. Along the way she transformed her identity – no longer was she ‘Barnaby Joyce’s wife’ but Natalie Joyce, successful body-builder.

Transformational practices are replete in the fitness industry and according to exercise psychologists, Buckworth and Dishman (2002), these promote the notion of self-regulation and individual responsibility. But such practices are attained when those seeking them have the right support. Especially women. In this context, Ms Joyce’s Personal Trainer should be heralded too.

Transformational practices are replete in the fitness industry and according to exercise psychologists, Buckworth and Dishman (2002), these promote the notion of self-regulation and individual responsibility. But such practices are attained when those seeking them have the right support. Especially women. In this context, Ms Joyce’s Personal Trainer should be heralded too.

Women’s experiences of transformational bodywork practices emerged in the 1990’s at the same time that Personal Trainers emerged in fitness culture. With the emergence of gym culture and physical activity landscapes changing, Jane Fonda had already enabled women to beat a path to the gym, which in the mid to late 1980’s opened their doors to women. Personal training followed and it wasn’t until 1991 that the first Personal Trainers emerged in fitness settings in New Zealand. [Sweet, 2008, 2017]. By the late 1990’s, body-transformation practices became lauded in fitness culture and women in my own study, enjoyed the new emphasis on exercise classes and personal training. With busy, complex lives, many believed that having a Personal Trainer was a necessary component of the requirement to not only stay on track, but also to feel supported and endorsed in the transformation they were seeking.

Women have complex lives, even more so when they arrive in mid-life. Ms Joyce is 49. I spoke about this with my fellow Row 3 passenger. As a high-profile female CEO in Australia, she bemoaned the fact that just the previous day she had to be in a senate hearing until 11pm at night. Gone was the start to the holidays with her children and gone was any chance of getting to the gym. The only solace she found was the supportive phone call she received from a board director thanking her for the work and the time she was putting in to be in Canberra when she should have been on holiday with her kids.

Because of our complex lives, women need support. In the exercise context, Ms Joyce’s support came in the form of a Personal Trainer. And in time, her Personal Trainer influenced her to attain what she might have thought was ‘impossible’ – standing on stage in a body-building competition. Her Trainer therefore, was a major influence on her new post-Barnaby identity.

Because of our complex lives, women need support. In the exercise context, Ms Joyce’s support came in the form of a Personal Trainer. And in time, her Personal Trainer influenced her to attain what she might have thought was ‘impossible’ – standing on stage in a body-building competition. Her Trainer therefore, was a major influence on her new post-Barnaby identity.

Personal Training is a shared venture and by the very nature of the client-trainer relationship, the role of a Trainer ultimately becomes located in a position of power. Social media ‘speak’ might call a good PT an ‘influencer’ in fact and it didn’t go un-noticed by the two of us in Row 3 on the flight to Sydney, that on the very next page was an article about Kendall Jenner, [she of Kardashian fame], and her little trip down-under to open the new Tiffany store. She was paid a cool half a mill for her efforts. But I digress – let’s get back to less well paid ‘influencers’ – Personal Trainers. ???? I know a bit about personal training. In 1991, I established the Personal Training industry in New Zealand for the Les Mills group – at a time when no personal training industry existed. Now there are thousands of PT’s throughout New Zealand and Australia and for that matter around the world. I’ve moved on from gym culture these days, but my own expertise, motivation and support can be found online in the MyMT programmes.

![MyMT Dr Wendy Sweet [PhD]](https://www.mymenopausetransformation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MyMT_Wendy_Banner_Oct_20182-300x169.png) Personal Trainers are powerful ‘influencers’. Good Personal Trainers have the capacity to create systems of thought that can exert considerable influence over people’s lives. Foucault (1988) refers to this as ‘technologies of the self’. As he states,

Personal Trainers are powerful ‘influencers’. Good Personal Trainers have the capacity to create systems of thought that can exert considerable influence over people’s lives. Foucault (1988) refers to this as ‘technologies of the self’. As he states,

‘individuals effect by their own means, or with the help of others, a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct and ways of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection of immortality.’

In the gym, Ms Joyce’s Personal Trainer shared the power of disciplined training and eating to not only change the physical body, but to change the mind and challenge the dominant identity that Ms Joyce had internalised for the past 24 years – wife of politician, Barnaby Joyce. But as Ms Joyce self-declared in the article, she isn’t this person any more. The routines and constant support mechanisms, established by her Personal Trainer chipped and chiselled away week on week, enabling and empowering her that yes, she could do this body-building competition. It was a masterclass in self-efficacy building (self-confidence towards task-mastery) guided, supported and motivated by her Personal Trainer.

Low self-efficacy for exercise is a known characteristic for women who give up on exercise. It’s the same for weight loss or any health changes.

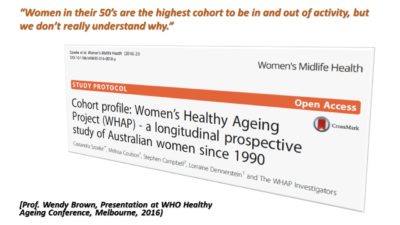

When women feel that they can’t succeed, they simply drop-out. It all becomes too hard and with physical activity and health data in New Zealand and Australia showing that mid-life women are the highest demographic to drop out of exercise participation (along with teenage females), there is something to be said about the role of a Personal Trainer. This person is only partly there to provide technical insight. For women, I suggest that one of the main roles of a PT is also to provide emotional and motivational support.

Increasing efforts have been made politically and economically to position and promote physical activity in the paradigm of exercise prescription – you know, write down ‘walk 3 times a week’ and people will adhere to it. But they don’t. And for women especially, for the past 3 decades, physical activity participation data shows that lack of time, lack of motivation and lack of energy are the three main influences on not being active enough for health benefits. But mid-life women need more than this written prescription and my own women’s healthy ageing studies reflected this too. Women who trained with a Personal Trainer found that their exercise had greater meaning because of the relationship each had with the person who gave them the most support, encouragement and accountability with their exercise – their Personal Trainer. It’s the same with many women on the MyMT programmes – they need knowledge, support and motivation too.

Midlife for all women is a time of transition and change, not only due to menopause but also with other influences, such as children leaving home (or staying!), ageing parents to care for, financial concerns and often, changes to personal and working circumstances to navigate as well.

Staying engaged with exercise is important and many women who have been active all their lives, find that this time of life is particularly challenging for maintaining their active status and therefore, their identity as physically-active women. This is a shame, because social science research is replete with studies reporting that when mid-life and older women participate in exercise or any other physical activity that makes them feel good about themselves and when they get the right emotional and motivational support, then they derive meaning from this and therefore, continue.

As both of us working girls’ in Row 3 on the flight between Canberra and Sydney opined on the account by the young journalist about Natalie Joyce’s ‘revenge body’, I reflected on my own women’s healthy ageing study about women and the meanings they derived from having Personal Trainers in mid-life and offered the comment that the journalist had got the story wrong. The true hero wasn’t Natalie Joyce and the rediscovery of her identity through a ‘revenge body’ which she then took to the stage.

The true hero was her Personal Trainer and the support, motivation and knowledge she provided for helping Ms Joyce find her new mid-life identity.

Seat 3A agreed.

References:

Ballard, K., Eslton, M-A., & Gabe, J. (2005). Beyond the mask: Women’s experiences of public and private ageing during midlife and their use of age-resisting activities. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 9(2), 169-187.

Brabazon, T. (2006). Fitness is a feminist issue. Australian Feminist Studies, 21(49), 65-83.

Brown, W., Kristiann, C., Heesch P. & Miller, Y. (2009). Life events and changing physical activity patterns in women at different life stages. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 37, 294-305.

Buckworth, J., & Dishman, R. (2002). Exercise psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Carr, A., Biggs S. & Kimberley, H. (2015). Aging, diversity and the meaning(s) of later life. Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice, 7(1), 7- 60.

Codina, N., Pestana, J. & Armadens, I. (2013). Physical activity among middle-aged women: Initial and current influences and patterns of participation. Journal of Women & Aging, 25(3), 260-272.

de Medeiros, K. (2005). The complementary self: Multiple perspectives on the aging person. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(1), 1-13.

Dionigi, R.A., Horton, S. & Bellamy, J. (2011). Meanings of aging among older Canadian women of varying activity levels. Leisure Sciences, 33(5), 402-419.

Codina, N., Pestana, J. & Armadens, I. (2013). Physical activity among middle-aged women: Initial and current influences and patterns of participation. Journal of Women & Aging, 25(3), 260-272.

Crossley, N. (2006). In the gym: Motives, meaning and moral careers. Body & Society, 12(3), 23-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X06067154

de Medeiros, K. (2005). The complementary self: Multiple perspectives on the aging person. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(1), 1-13.

Diehl, M., Wahl, H., Brothers, A., & Miche, M. (2015). Subjective aging and awareness of aging: Toward a new understanding of the aging self. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 35, 1-X.

Eyler, A., Brownson, R., Donatelle, R., King, A., Brown, D. & Sallis, J. (1999). Physical activity, social support and middle-older-aged minority women: results from a U.S. survey. [Electronic version]. Social Science & Medicine, 49(6), 781-789.

Fonda, J. (2011). Prime time. Croydon, UK: Random House.

Foucault, M. (1988). ‘Technologies of the self’. In L.H. Martin, H. Gutman & P. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault, Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Frew, M. & McGillivray, D. (2005). Health clubs and body politics: Aesthetics and the quest for physical capital. Leisure Studies, 24(2), 161-175.

Garrin, J. (2014). Self-efficacy, self determination, and self regulation: The role of the fitness professional in social change agency. Journal of Social Change, 6(1), 41-54.

Glassner, B. (1989). Fitness and the postmodern self. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30(2), 180-191.

Hardcastle S. & Hagger, M. (2011). “You can’t do it on your own”: Experiences of motivational interviewing intervention on physical activity and dietary behaviour. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 314-323.

Henderson, K., Hodges, S. & Kivel, B. (2002). Context and dialogue on women and leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(3), 253-271.

Hentges, S. (2014). Women and fitness in American culture. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Higgs, P., & Gilleard, C. (2015). Fitness and consumerism in later life. In Tulle, E. and Phoenix, C. (Eds.), Physical activity and sport in later life (pp. 32-42). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Hurd-Clarke, L. (2001). Older women’s bodies and the self: The construction of identity in later life. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 38(4), 441-464.

Kennedy, E. & Markula, P. (2011). Women and exercise: The body, health and consumerism. Oxford, UK: Taylor and Francis.

Kretchmar, R. S. (2007). What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st Century. Quest, 59, 373–383.

Lachman, M., Teshale, S., & Agrigoroaei, S. (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course. International Journal of Behavioral Development,39(1), 20-31.

Lucke, J., Brown, W., Tooth, L., Loxton, D., Byles, J., Spallek, M. Powers, J., Hockey, R, Pachana, N. & Dobson, A. (2010). Health across generations: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Biological Research for Nursing, 12(2), 162-170.

Madeson, M., Hultquist, C., Church, A. & Fisher, L. (2010). A phenomenological investigation of women’s experiences with personal training. International Journal of Exercise Science, 3(3), 157-169.

Marshall, C., Lengyel C., & Menec, V. (2014). Body image and body work among older women. Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care, 7(4), 198-210.

Ministry of Health [MOH] (2012). The health of New Zealand adults 2011/2012. Key findings of the New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Partington, E., Partington, S., Fishwick, L., & Allin, L. (2005). Mid-life nuances and negotiations: narrative maps and the social construction of mid-life in sport and physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 10(1), 85-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/135733205200098820

Radtke, L.,Young, J., & van Mens-Verhulst, J. (2016). Aging, identity and women: Constructing the third age. Women & Therapy, 39(1), 86-105.

Sassatelli, R. (2010). Fitness culture: Gyms and the commercialisation of discipline and fun. Hampshire, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Saucier, M. (2004). Mid-life and beyond: Issues for aging women. Journal of Counselling and Development, 82(4), 420-425.

Smith deJulio, K., Windsor C. & Anderson, D. (2010). The shaping of midlife women’s views of health and health behaviours. Qualitative Health Research, 20(7), 966-976

Smith Maguire, J. (2008). The personal is professional: Personal trainers as a case study of cultural intermediaries. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 11(2), 211- 229.

Sweet, W. (2008). Personal Trainers: Motivating and moderating client exercise behaviour. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Sweet, W. (2017). It’s personal and it’s professional: The meanings women Baby-boomers attribute to their ageing and ‘working-out’ with a Personal Trainer. Doctoral thesis: University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Tulle, E., & Dorrer, N. (2011). Back from the brink: Ageing, exercise and health in a small gym. Ageing & Society, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.107/S0144686X11000742

Tulle, E., & Phoenix, C. (Eds.). (2015). Physical activity and sport in later life: Critical perspectives. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Twigg, J. (2004). The body, gender, and age: Feminist insights in social gerontology. Journal of Aging Studies 18(1), 59–73.

World Health Organisation (2009). Women and Health. Today’s evidence. Tomorrow’s agenda. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.