Imagine the confusion and frustration felt by Lyn, (in the photo), when what you’ve done for years in terms of your workouts, no longer works for you. You’re pulling together the complexity of your training regime, nutrition and supplements, taking the advice of your Trainer, but there’s something not quite right.

You’re not sleeping well, your gut health is playing up, your blood sugar is crashing frequently based on your monitoring and your hot flushes are through the roof.

“Menopause changes your muscles and your blood pressure Lyn and doesn’t take notice of whether you are a bodybuilder or not” was the first thing I mentioned when she shared her experience about her blood sugar crashes after dinner (post-prandial), in my coaching community. She felt that she wasn’t keeping on top of her glucose requirements after training and her blood sugar levels which she was monitoring weren’t stable.

Lyn was mystified, and had been searching for answers. But I told her it was normal during menopause to have blood glucose regulation problems … especially when your muscles are ageing and changing when you reach your 50s and the fact that she was doing heavy resistance training workouts to get the physique she needed to compete.

You see, even despite the training that Lyn was doing to facilitate muscle growth, menopause hormonal changes don’t differentiate between athletes or not! Numerous changes in both muscle mass and strength occur as hormone levels change during and after menopause. This is due to the effect of oestrogens on muscles, nerves and blood vessels.

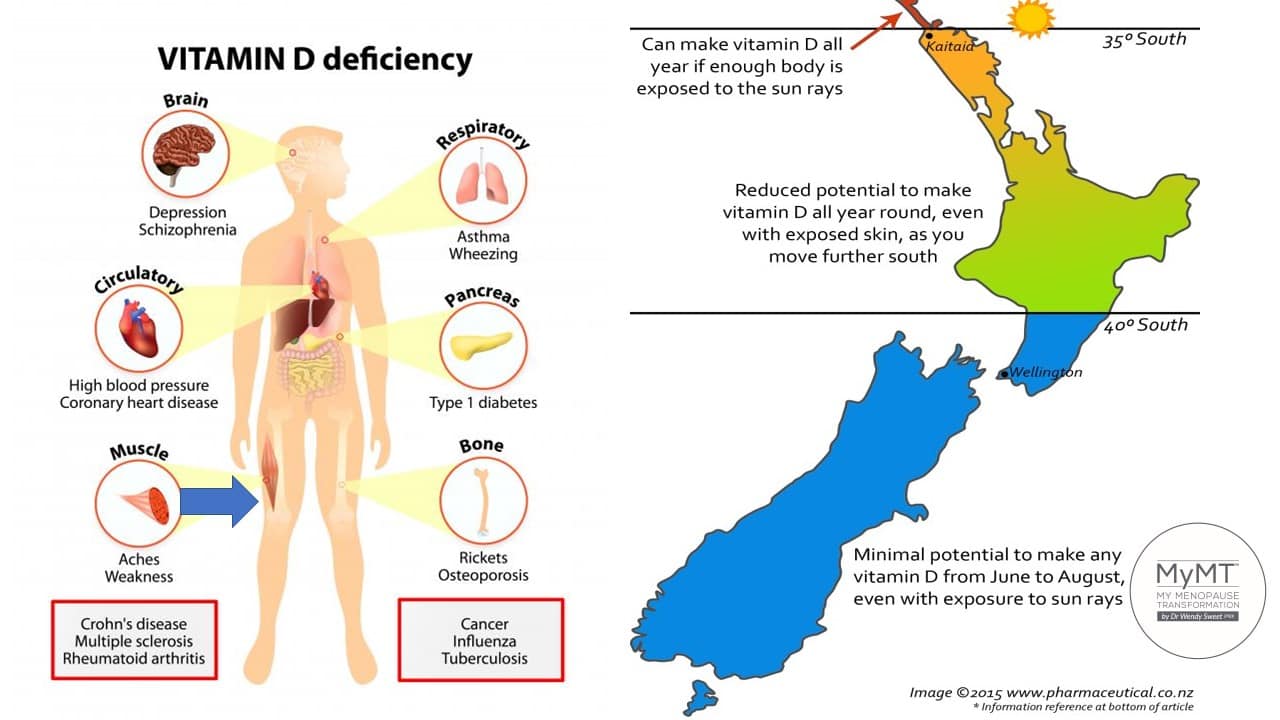

Women who are doing heavy workouts as Lyn does, may need to examine how well they recover, as well as their Vitamin D levels. New research suggests that this affects muscle contraction capability and recovery too. Iron levels are equally important, as is nutrition and the increased need for soy isoflavones for recovery.

Women who workout and who are transitioning through perimenopause might also need to explore Menopause HRT with their Doctor. Afterall, when you are growing muscle mass as Lyn is, oestrogen plays a crucial role in this process.

It’s a different game for women who work out and thanks to Lyn, who has just come on board my programme, this is the topic of my Wednesday briefing for you this week. I invited her to share her competition photos with you and she kindly did.

Whether you work-out or not, understanding that our menopause transition is associated with a natural decline in muscle mass and strength is important. Menopause also changes our blood vessels and for some of you, heavy resistance training can cause hypertension (high blood pressure).

The blood pressure response to resistance training depends on a number of factors including the amount of muscle mass recruited, breathing technique, amount of resistance lifted, number of repetitions, speed of lifting and rest between sets.

Furthermore, the Cooper Aerobic Institute, a highly respected exercise and sport science research institute, suggest that when blood pressure is known to be high, the more muscle mass used during a resistance training exercise, the greater the blood pressure response.

This is important to note for women who aren’t sleeping. When insomnia arrives during our menopause transition, exercise tolerance is lowered, because blood pressure remains higher than usual. This means that numerous women who are regular exercisers and not sleeping during their menopause transition, can be thrown into over-training syndrome more easily than in the past.

One of the most frequent questions I receive is to do with muscle mass gains during menopause. How can we prevent the loss of muscle (known as sarcopenia)? Can we over-ride sarcopenia with resistance training? Well, yes we can … but only to some extent – and this depends on so many other factors, including:

- Whether you are sleeping for at least 7-8 hours each night. Sleep helps with the regulation of growth hormone production, which is involved in pathways that help tissue anabolism (growth), including muscles.

- Which stage of menopause you are in. In peri-menopause, your ovaries (if you have them) are still producing oestrogen and progesterone, and this assists in muscle mass and strength. But if you’re in post-menopause, then you don’t have the benefit of higher levels of reproductive hormones. Your muscles also start to lose their power fibres (Type 2) as you move into post-menopause.

- Whether you have optimal Vitamin D levels. This powerful nutrient is now understood to be a hormone and it is involved in calcium absorption. Calcium plays a crucial role in muscle contraction and power output when you are training.

- Whether your iron levels or stored iron (ferritin) are optimal. Optimal iron levels are a pre-requisite mineral for sleep as well as improved oxygen delivery to working muscles. If you aren’t recovering or you feel more breathless, or your hot flushes are through the roof (as Lyn’s were too), or you have very low body fat, then get your iron and ferritin levels checked. It is well known in sport and exercise science research, that low iron (or high iron in post-menopause) are a cause of hot flushes in athletes and extremely low body fat percentage causes disruptions to monthly menstrual cycles. Known as the female athlete triad, it is an increasingly recognized cause in those who participate in intense athletic activity or have low body fat.

- Whether you have enough, or too much protein in your diet. Having too much protein increases your risk for gut, renal and liver inflammation.

- Whether you are recovering, resting and ‘cycling’ your training routine. Women in menopause may take longer to recover, especially if liver and gut health isn’t ideal. Inflammatory changes during menopause in the gut and liver, affects the absorption of nutrients such as B-vitamins, which are involved in numerous energy regulation and production pathways.

- Whether you are having enough healthy carbohydrates in your diet. Many athletes are so focused on proteins and fats these days, that women in menopause may be being advised to increase their intake of fats and protein to the detriment of beautiful energy-giving carbohydrates. These not only help you to replace vital glucose into liver and muscle cells to help your recovery, thus helping you to restore your stored glucose (glycogen) levels ready for your next training bout, but certain types of carbohydrate, help your gut health by giving you resistant starch.

- Whether you are on Menopause HRT or not. Some evidence suggests that women in perimenopause or menopause who are training competitively, may benefit from oestrogen replacement in order to retain muscle mass and strength. [Maltais & Dionne, 2009].

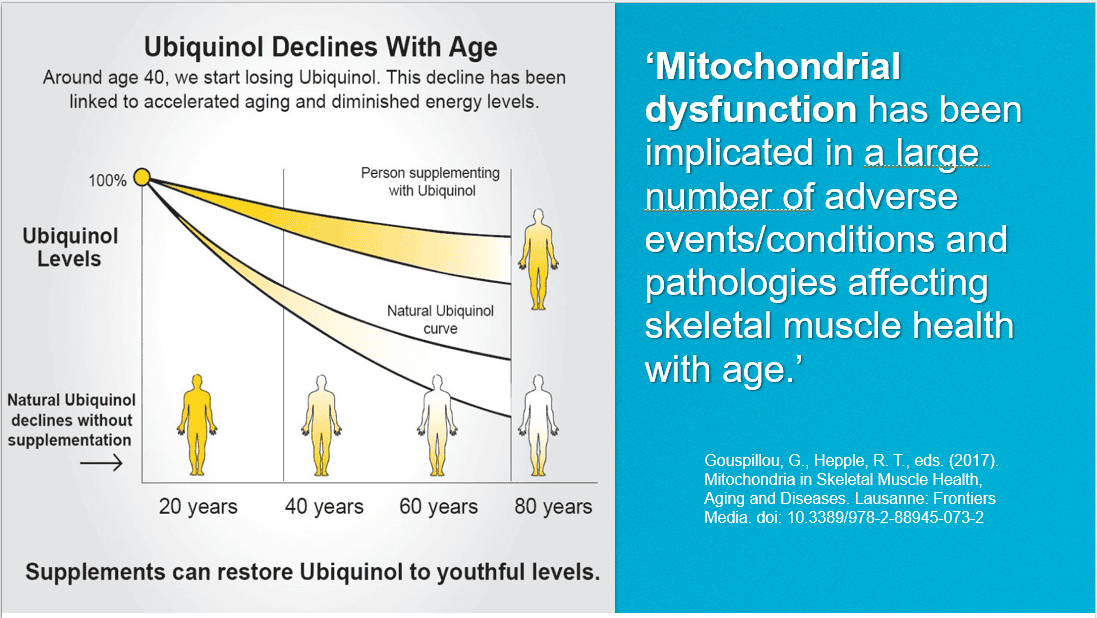

- Whether you are having the correct supplements for your ageing muscles, including your heart. Many athletes need supplements, purely because they can’t get enough nutrients into them to replace and repair metabolic training and competition demands. Women in menopause are no exception. I’m not talking about protein powders either. I’m talking about your intake of B vitamins, for your energy; Vitamin C, which helps to repair collagen that you are breaking down in your heavy training bouts and CoQ10 for your ageing heart – afterall, this is a muscle that bears the brunt of heavy training such as resistance training, as well. I call the heart and blood vessels, the ‘forgotten factor’ in understanding how and why our response changes when working out in menopause or post-menopause. I talk about this in my online Masterclass on Menopause.

Changes in Muscle Mass and Tissue in Menopause

Menopause – the universal cessation of human female fertility at around age 50 – presents an intriguing evolutionary puzzle for scientists and women alike. But as Bengston et al (2005) state,

“Ageing is highly complex, involving multiple mechanisms at different levels. The most important mechanisms are linked via endogenous (external) stress-induced DNA damage … (and) understanding how such damage contributes to age-related changes requires that we explain how these different mechanisms relate to each other and potentially interact.” [p. 75].

This is the view that I take with menopause … as I’m always saying to women, ‘menopause isn’t just about hot flushes’.

There are so many other issues that impact on symptoms rather than just declining hormones which of course, in menopause is a natural event in our life-course.

What we do each day of our life and how we live our life affects our symptoms too. This includes how long we’ve been exercising, how hard we exercise, the type of exercise we choose to do, how much stress we have in our day-to-day life, how well we recover from day to day and how much inflammation has built up in cells and tissues over our lifetime.

This is what I explained to Lyn. As someone who has had years of competitive exercise, she is carrying muscular and myofascial inflammation into her menopause transition. Add to this, her insomnia and hot flushes, and this creates more inflammatory changes in both muscle tissue and the outer sheath surrounding it, called the myofascia.

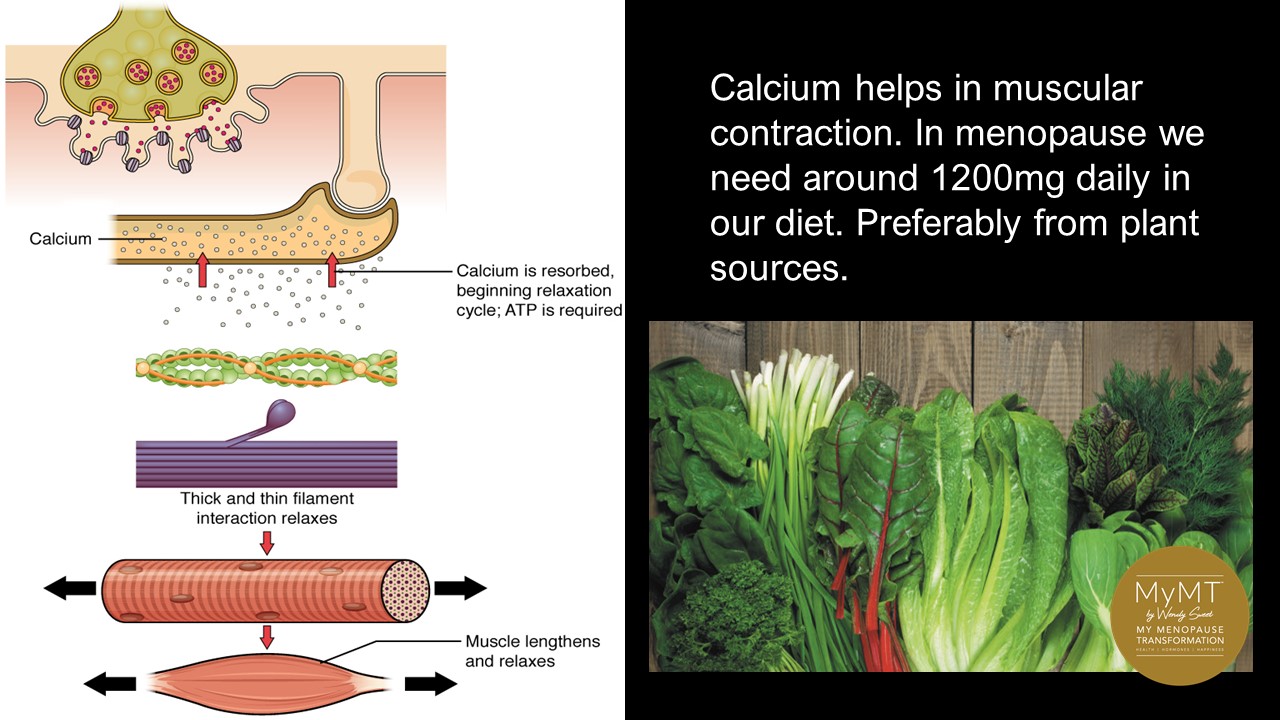

Chronic stress from insomnia and night sweats, as well as inflammation from heavy training, and low absorption of calcium if gut health problems are present or if Vitamin D is low, can create a vicious cycle of poor muscle recovery from training for competitive athletes, whether they are body-builders or not.

Therefore, having regular myofascial release work or massage is an important training and recovery strategy for women who workout. If you’re intent in being an athlete as you age, then please add massages to your budget because as I explain below, your muscles and your muscle contractile properties, are changing during and after menopause.

Although the literature is only just emerging about women and heavy exercise during menopause, it is well known that whatever the training state of women in menopause and post-menopause, muscle mass in women tends to decrease gradually after the 3rd decade of age. After the 5th decade of age, an accelerated decline occurs with the changes in oestrogen and progesterone production – this is inevitable, be it due to age or menopause.

One of the most important changes to muscles during our menopause transition, has to do with the decline in our Type 2 fibres – these fibres are our power and strength fibres which affect muscle mass and strength. They rely on oestrogen. These fibres are full of oestrogen receptors which work closely with oestrogen and IGF-1(this is a hormone called Insulin-like growth factor 1. It functions as the major mediator of Growth Hormone, which helps to maintain and build tissue size, such as in muscles).

The loss of muscle mass and strength as women age, also occurs partly due to changes to our nerves and the neuro-muscular junction which controls muscle contraction. In this respect, calcium intake is as important as protein intake for women who have a high volume of activity. If you experience restless leg syndrome, then look at your calcium intake as well as your Vitamin D levels. Calcium helps nerves to ‘jump’ their messages across into muscles and this helps to improve our muscle speed, strength, balance and reaction time. It’s why I told Lyn that she needs to get her levels checked because she trains as a bodybuilder.

Many women who are training heavily don’t associate menopause with changing skin and Vitamin D absorption – as such, they don’t associate low Vitamin D levels with their recovery after exercise, especially if muscle growth is the intended purpose of the training as in the case of Lyn.

Vitamin D is involved in processes related to immune function, such as inflammation. However, it’s also involved in muscle tissue recovery and plays an active role in the muscle inflammatory response, protein synthesis, and regulation of skeletal muscle function. One of the target tissues for vitamin D is skeletal muscle, so if you have gut health concerns, then you may not be absorbing enough calcium for all of your muscle contractions if Vitamin D is low.

Vitamin D and calcium absorption in your small intestine, go hand in hand, whether you are an ageing athlete or a recreational exerciser as I am these days too, perhaps get your levels checked, especially as the Southern Hemisphere moves into winter.

Our menopause transition is a critical time to introduce strategies to mitigate the changes in muscle mass and function that contribute to physical disability and frailty later in life. But many of us find that our joints and muscles ache and we don’t have the time, energy or motivation to exercise. Physical activity participation research supports this in midlife too.

However, the right amount and type of exercise during menopause can assist us into improved health as we age. Therefore, we have to progressively explore turning around our symptoms so that we sleep all night, lose some weight if we need to and reduce the rate of muscle loss and weakness.

We all know that physical activity is ‘good’ for us. And no, we don’t have to do the volume and intensity of exercise that Lyn does with her bodybuilding! But if we can do enough exercise to promote mitochondrial health, increase protein turnover in muscles, thus aiding repair, and restore nerve signaling involved in muscle contraction and function, through moderate aerobic activity and 2-3 resistance training workouts a week, then we will all reap the benefits.

Ageing has become an important topic for scientific research, including muscular and strength research because life expectancy and the number of men and women in older age groups have increased dramatically in the last century.

Muscle strength and function is an increasingly important topic in exercise science, because by 2050, the world’s population over 60 years will double from about 11% to 22%. This means that there will be 2 billion people aged 60 or older living on this planet. Approximately 400 million will be 80 years or older, over half of them women.

Furthermore, women are having to work in paid work for longer and therefore, we have to not only remain relevant as we move into midlife, but we also have to boost our resilience. Maintaining lean muscle mass is one way to achieve this. Understanding how much your muscle strength and function change as you age matters.

It took me a long time to figure out why I wasn’t able to do the harder, more powerful skiing that I used to be able to do. But as soon as I looked at menopause through the lens of our biological ageing, I knew I would find the answer when I better understood what happens to our muscles as we age as Lyn and other women exercisers who join me on my programmes, including my 12 week Rebuild My Fitness programme, are discovering too.

References:

Bengtson, V., Coleman, P & Kirkwood, T. (2005). The Cambridge Handbook of Age and Ageing. Ed. Johnson, M. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brunner, F., Schmidt et.al. (2007). Effects of aging on Type II muscle fibers: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Ageing & Physical Activity, July;15(3):336-48.

Caballero-García, A., Córdova-Martínez, A. et al. (2021). Vitamin D – Its role in recovery after muscular damage following exercise. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072336

Butler-Browne, G., Mouly V., et al, (2018). How Muscles Age, and How Exercise Can Slow It. The Scientist Online Edition.

Ko, J., & Park, Y. M. (2021). Menopause and the Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Women. Iranian journal of public health, 50(2), 413–414. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i2.5362

Maltais ML, Desroches J, Dionne IJ. (2009). Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. Oct-Dec;9(4):186-97. PMID: 19949277.

Pierre, T. & Pizzo, P. (2018). The Ageing Mitochondria, Genes, 9, 22; doi:10.3390/genes9010022