“Since my body-building competition, I’ve been trying to grow muscle, but all I’ve gained is 6kg of mainly fat. My liver had become very unhealthy”. [Lyn, Australia]

What your clients do each day of their life and how they live their life affects symptoms in menopause. I’m often telling my own clients this, including former body-builder, Lyn, from Australia.

Since the early 1990s the exercise industry has been expanding rapidly. As greater emphasis has been placed on strength and conditioning, more and more women have been enjoying heavy weight training.

I know this, because back then, I pioneered the personal training industry for global fitness giant, Les Mills.

At the time, exercise-to-music classes were evolving and the emergence of barbell classes, which Les Mills labelled ‘BodyPump’. Alongside this, the number of women who were working out in the gym with Personal Trainers was emerging too.

With the trend towards more advanced resistance-training workouts for women, there are many of us who have participated in these types of workouts for decades. Interviews that I undertook for my doctoral studies revealed that these workouts helped women cope with their busy, stressful lives.

However, what the women on my studies also shared with me was that when they reached their mid-40s and early 50s, although they were undertaking the same heavy workouts, they felt exhausted. Hot flushes became worse, sore joints and muscles distracted them and a full night’s sleep was a distant memory.

Body-builder, Lyn was the same.

How Lifestyle Factors Impact Menopause Symptoms and Training Tolerance

How long your clients have been exercising, how hard they exercise, the type of exercise they choose to do, how much stress they have in their day-to-day lives, how well they recover from day to day, including how much sleep they get, and how much inflammation has built up in organs such as their liver and gut, and in muscles and joints, all impact the frequency and severity of menopause symptoms.

This is what I explained to Lyn. As someone who has had years of competitive, heavy training, Lyn was carrying muscular and joint inflammation into her menopause transition. Her liver, having had to turn over a lot of glucose and amino acids to assist both exercise and recovery needs, was also inflamed.

She had no idea that menopause hormonal changes would have such an effect on her tolerance to her training.

I see this a lot in my own clients. Many are pushing through with their training, despite not sleeping. However, this contributes to inflammatory changes and increased oxidative stress in muscles, the myofascia (the outer sheath surrounding muscles) and in the liver and gut.

Changes in Muscle Mass and Tissue in Menopause

If you have clients who are regular gym-goers and heavy-lifters, but they aren’t sleeping, they have IBS, they feel fatigued and their hot flushes/ flashes have increased in frequency and severity, (whether or not they are on Menopause HRT), then perhaps it’s time for them to reduce the load and frequency of their workouts.

This is something that I advise in my own programmes, and it’s perhaps one of the hardest behaviours for seasoned exercisers to do!

Numerous changes in both muscle mass and strength occur as hormone levels change during and after menopause. This is due to the effect of oestrogens on muscles, nerves and blood vessels.

Women who are doing heavy workouts, as Lyn used to do, often feel exhausted. But because they have been training for years, they have high pain tolerance due to the necessity to build-up lactic acid during their heavy training. Many don’t understand that their recovery strategies may need to change during menopause.

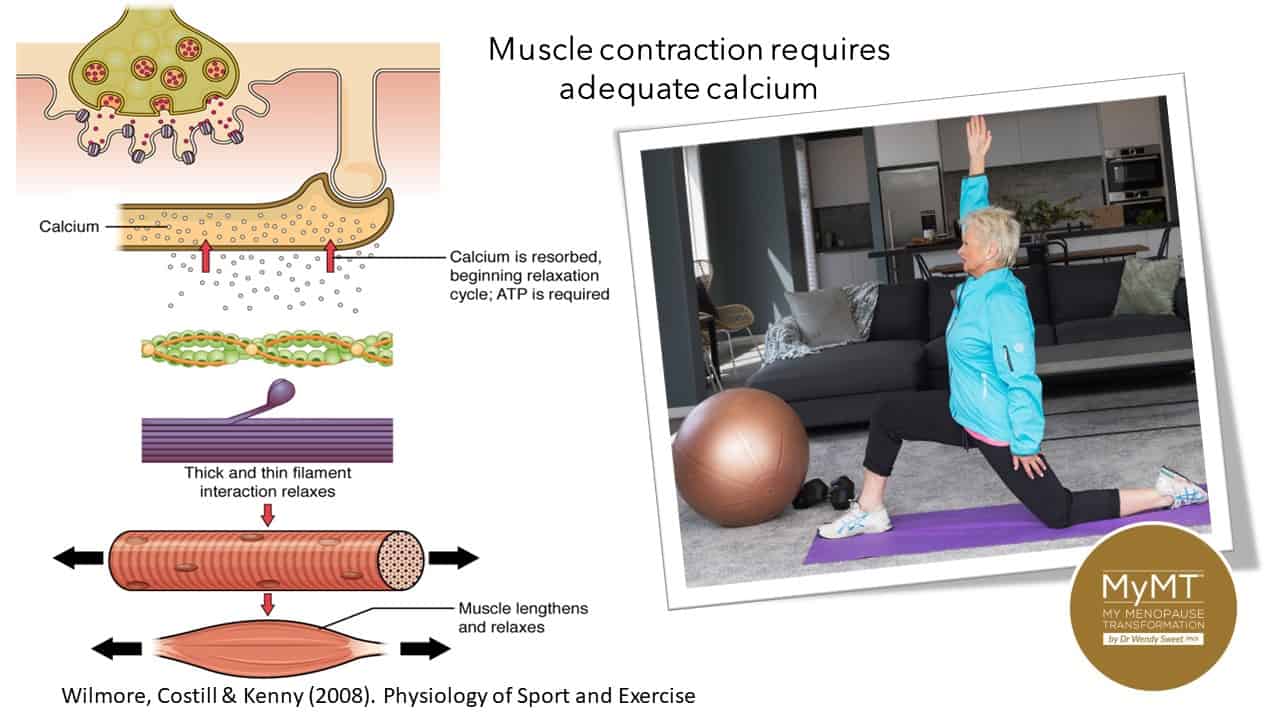

This includes understanding that if their Vitamin D levels, are not optimal, this can impact muscle contraction capability and their ability to recover. Simply because Vitamin D aids in calcium absorption in the small intestine. Calcium is a neuro-transmitter, helping in the neuro-muscular contraction pathway.

With low Vitamin D levels, muscle contractile force is reduced because Vitamin D works on the Type 2B power fibres. (Maltais, 2009). Recovery is also impacted when Vitamin D is low, because this impacts muscle uptake of calcium – an essential requirement in the neuro-muscular pathway.

Chronic stress from insomnia and night sweats, as well as inflammation from heavy training, and low absorption of calcium if gut health problems are present or if Vitamin D is low, can create a vicious cycle of poor muscle recovery from training for menopausal women, whether they are competent exercisers or not.

Iron levels are also equally important, as is nutrition and the increased need for soy isoflavones for recovery.

Do your clients need Menopause HRT?

Women who workout and who are transitioning through perimenopause might also need to explore Menopause HRT with their Doctor. Afterall, when you are growing muscle mass as Lyn was, oestrogen plays a crucial role in this process.

The Impact of Menopause on Muscle Mass and Recovery: Understanding the Role of Hormones and Sleep

Although the literature has only recently emerged about women and the effects of heavy exercise during menopause, it is well known that whatever the training state of women in menopause and post-menopause, muscle mass in women tends to decrease gradually after the 3rd decade of age.

After the 5th decade of age, an accelerated decline occurs with the changes in oestrogen and progesterone production – this is inevitable, be it due to age or menopause.

One of the most important changes to muscles during the menopause transition, has to do with the decline in Type 2 fibres – these fibres are our power and strength fibres which affect muscle mass and strength.

Type 2B fibres rely on oestrogen and have high numbers of oestrogen receptors which work closely with oestrogen and IGF-1. This is a hormone called Insulin-like growth factor 1, which functions as the major mediator of Growth Hormone, which helps to maintain and build muscle tissue size.

If your clients aren’t sleeping night after night, then this impacts their recovery from their workouts and their ability to grow new muscle.

This is because Growth hormone (GH) is secreted as a series of pulses throughout the 24-h cycle and in normal adult subjects, the most reproducible and often the largest GH pulse occurs during early sleep, with the first phase of deep slow-wave sleep (SWS). [Graf, 2019].

And it’s not just women lifting weights that are impacted by poor recovery following exercise. It’s midlife endurance athletes as well.

Why Heavy Weight Lifting and Intense Workouts Aren’t Suitable for Everyone During Menopause

Heavy weight lifting and intense workouts aren’t for everyone.

Especially clients who have been training for decades and have embedded and normalised the type and volume of training they are doing, without any consideration for the skeleto-muscular and neuro-muscular changes occurring during the menopause transition.

Physical activity participation research supports that the midlife transition is a critical window for women dropping out of exercise. For many, this is because they feel exhausted, having aching muscles and joints and of course, may not be sleeping.

However, the right amount and type of exercise during menopause can assist women into improved health as we age. We all know this.

Therefore, as Practitioners, we have to progressively explore turning around client symptoms so that they sleep all night, improve their liver health (where amino acids are turned over which are required for muscle repair and hypertrophy), improve gut health and reduce the rate of muscle loss and weakness.

I’m often saying to my own clients that ‘Exercise should be energising, not exhausting‘. For many of your clients who aren’t sleeping well, or aren’t recovering well from their workouts, this may mean helping them understand that ‘less is more’ in the longer term.

That’s why I recommend the exercise recommendations on the American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Physical Exercise for women as they age as a starting point.

This includes promoting enough exercise to achieve mitochondrial health and increased protein turnover in muscles, thus aiding repair, and enhancing neural recruitment of muscles.

The guidelines recommend moderate aerobic activity on at least 5 days per week and 2-3 resistance training workouts a week, including one HIIT session as well as flexibility, balance and gait exercises.

A good body of evidence supports the decline in muscle mass during the menopause transition and for many women, this is an important time to begin a regular exercise routine.

However, for those women who have been training for decades and are in danger, of ‘over-training’ because they aren’t sleeping and aren’t recovering well from their existing training regime, then it’s also a time to turn-down the intensity and volume of exercise, especially when it comes to heavy weight training, until they have addressed their underlying symptoms, including sleep.

It took me a long time to figure out why I wasn’t able to do the harder, more powerful skiing that I used to be able to do.

But as soon as I looked at menopause through the lens of our biological ageing, I knew I would find the answer when I better understood what happens to our muscles as we age as Lyn and other women exercisers who join me on my own programmes, have discovered too.

I hope that you can join me on any of the MyMT™ Education certified courses – we are taking pre-registrations now for the September intake of the Practitioner course too, so please make sure you visit the link HERE to pre-register your interest.

REFERENCES:

American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Mar;41(3):687-708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670.

Bengtson, V., Coleman, P & Kirkwood, T. (2005). The Cambridge Handbook of Age and Ageing. Ed. Johnson, M. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brunner, F., Schmidt et.al. (2007). Effects of aging on Type II muscle fibers: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Ageing & Physical Activity, July;15(3):336-48.

Butler-Browne, G., Mouly V., et al, (2018). How Muscles Age, and How Exercise Can Slow It. The Scientist Online Edition.

Caballero-García, A., Córdova-Martínez, A. et al. (2021). Vitamin D – Its role in recovery after muscular damage following exercise. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072336

Consitt LA, Copeland JL, Tremblay MS. Endogenous anabolic hormone responses to endurance versus resistance exercise and training in women. Sports Med. 2002;32(1):1-22. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232010-00001.

Graf, A. (2019). Sourced from: https://www.endocrinology.org/endocrinologist/134-winter19/features/24-hours-in-the-life-of-a-hormone-what-time-is-the-right-time-for-a-pituitary-function-test/

Ko, J., & Park, Y. M. (2021). Menopause and the Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Women. Iranian journal of public health, 50(2), 413–414. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i2.5362

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Med. 2005;35(4):339-61. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535040-00004.

Maltais ML, Desroches J, Dionne IJ. (2009). Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. Oct-Dec;9(4):186-97. PMID: 19949277.

Miljkovic N, Lim JY, Miljkovic I, Frontera WR. Aging of skeletal muscle fibers. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015 Apr; 39(2):155-62. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.2.155. Epub 2015 Apr 24.

Pierre, T. & Pizzo, P. (2018). The Ageing Mitochondria, Genes, 9, 22; doi:10.3390/genes9010022

Takahashi Y, Kipnis DM, Daughaday WH. Growth hormone secretion during sleep. J Clin Invest. 1968 Sep;47(9):2079-90. doi: 10.1172/JCI105893.

Zouhal H, Jayavel A, Parasuraman K, Hayes LD, Tourny C, Rhibi F, Laher I, Abderrahman AB, Hackney AC. Effects of Exercise Training on Anabolic and Catabolic Hormones with Advanced Age: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2022 Jun;52(6):1353-1368. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01612-9.