It was quite a few years ago now that I heard an interview on New Zealand’s national radio about the rapid rise of obesity in the population. At the time I was lecturing in university level nutrition and health promotion and my ears were atuned to anything about overweight and obesity in the population.

I clearly remember the researcher talking about the geographical locations, ethnicity and age-specific cohorts that had the highest levels of overweight and obesity. I was stopped in my tracks when he said, that European/Pakeha women over the age of 50 living in certain parts of the North Island (Waikato and Hawkes Bay) were the highest group.

When I began to put on weight myself when I reached my late peri-menopause years, I remembered this interview. And yes, I was living in one of those regions at the time.

Demystifying overweight and obesity status during the menopause transition has been a personal interest of mine for the past decade. Not only because I needed to figure it out for my own health, but also because I needed to help other women figure it out as well.

Afterall, when women move from peri-menopause (when periods begin to fluctuate) to menopause (when periods end), they often experience another ‘shift’ in their weight gain. Many move from overweight status (a waist circumference between 80 – 88cm) to obese status (a waist circumfernce over 88 cm).

What Does Oxidative Stress in Fat Cells have to do with Menopause Weight Gain?

Weight gain associated with the menopause transition isn’t only about the change in hormone status as women move into their post-reproductive years. It’s also about the inflammatory changes that occur in fat cells which is known as oxidative stress.

The term ‘oxidative stress‘ is a phenomenon caused by an imbalance between the production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells and tissues which cause inflammation and subsequent damage to the cellular walls and lining, and the ability the body to manage this inflammation.

When oxidative stress or inflammation occurs in fat cells (adipose tissue) as well as in both liver and gut cells, then this creates a ‘perfect-storm’ for weight gain during menopause.

Then there is the role of excess oestrogens in women who are overweight or obese. Fat cells have an affinity for excess oestrogens.

You may be wondering why I’m talking about ‘excess oestrogens’ when menopause is the time of life where oestrogen production is declining? However, we can also obtain oestrogens from other sources, including animal products, chemicals, the conversion of cortisol when stress is high (physical and emotional), medications, and or course, contraceptives.

Furthermore, a major driver for developing obesity and metabolic dysfunction is the uncontrolled expansion of white adipose tissue (WAT). And herein lies the problem, which I didn’t know when I was putting on belly-fat too, and that is, that a critical determinant of body fat distribution and increased WAT is the sex steroid, oestrogen.

Hence, if women are already overweight or obese going into peri-menopause and then menopause and they are having too many oestrogens in their food, in chemicals (xeno-oestrogens) or in various medications, they may see their white fat level increase.

Deeper (visceral) WAT is often associated with metabolic dysfunction and pro-inflammation.

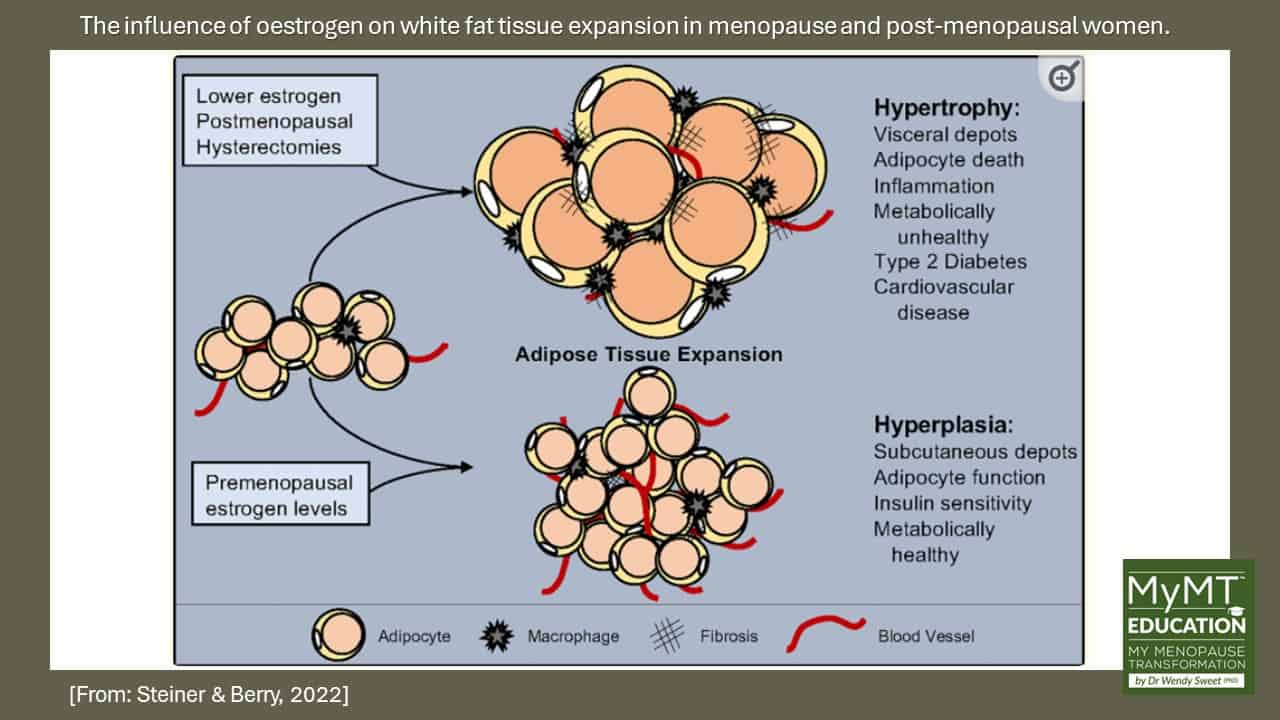

The image below demonstrates the influence of oestrogen on adipose (fat) tissue expansion. [Steiner & Berry, 2022]

Understand the two ways that fat cells expand – one is ‘healthy’, one is ‘unhealthy’ in menopausal and post-menopausal women:

White adipose tissue (WAT) can expand via:

(1) Hypertrophy – this refers to the swelling or enlargement of individual fat cells (adipocytes). Hypertrophy tends to occur as women move from menopause to post-menopause and the problem is that it reduces blood flow to the cells. This means that important oxygen can’t be delivered to the mitochondria very well – this promotes even more inflammation, or ‘oxidative stress‘ because fat-burning occurs in the mitochondria.

(2) Hyperplasia – this refers to the increase of adipocyte (fat cell) numbers and this tends to be the superficial fat. In healthy, normal weight women, the hyperplasia of fat cells maintains tissue health because it promotes increased blood vessels and therefore, helps oxygen be delivered, which in turn promotes anti-inflammatory signals.

While normal oestrogen levels (pre-menopause) result in hyperplastic subcutaneous adipose tissue growth, reduced oestrogen as women transition from peri-menopause to post-menopause, leads to metabolically unhealthy hypertrophic visceral adipose tissue expansion.

How do we turn unhealthy, inflamed hypertrophic fat cells into healthier hyperplasic fat cells?

There are three main ways to do this:

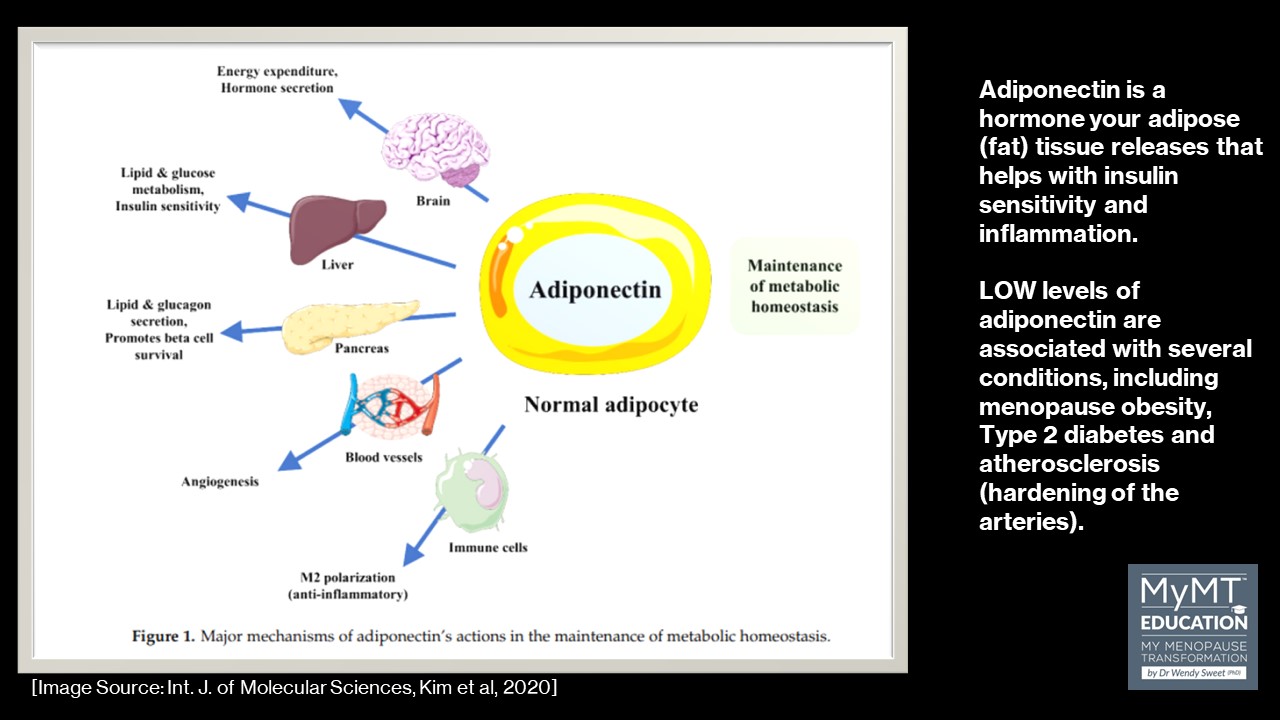

(1) Improve Adiponectin – this is a hormone your adipose (fat) tissue releases that helps with insulin sensitivity and inflammation. Low levels of adiponectin are associated with several conditions, including obesity, Type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

Adiponectin is secreted with the bioactive molecule leptin from normal adipose tissues (together, they are called adipokines). It regulates glucose and fatty acid metabolism by increasing insulin sensitivity of peripheral organs and muscles. This is important for weight management. And to increase adiponectin levels, the easiest way to do this (apart from some medications) is to increase your (or your clients) intake of healthy, Omega 3 fats – see below.

(2) Improve aerobic exercise – exercise has adipocyte-specific effects that may alleviate the adverse impact of oestrogen loss through the menopausal transition period and beyond. Exercise, especially aerobic exercise, remains the best therapeutic agent available to mitigate menopause-associated metabolic dysfunction, because one of the main functions of aerobic exercise is to facilitate more and larger mitochondria organelles. Aerobic exercise also increases capilliarisation and this is important for fat cells that are hypertrophied (enlarged), because larger fat cells have lowered vascularisation (blood vessels). Enhancing ways for your clients to become more active represents a vital behavioral strategy for you as a Health Practitioner and Health Coach or PT. How to achieve this in a progressive way with exercise prescription is in the MyMT™ Menopause Weight Loss Coach Course.

(3) Increase Omega 3 Fats, Vitamin C, Vitamin E and intake of Phytates – all of these foods help to increase adiponectin levels in the body, which in turn reduces inflammation in fat cells. Vitamin E is a fat-soluble antioxidant that stops the production of ROS formed when fat undergoes oxidation. Scientists are investigating whether, by limiting free-radical production and possibly through other mechanisms, vitamin E might help prevent or delay the chronic diseases associated with free radicals.

Overweight and obesity status are complex.

But one of the most relevant changes in metabolic science over the past decade has been the recognition that adipose (fat) tissue is no longer viewed as a passive source of free fatty acids, but instead, it is hormonally active. [Di Domenico et al (2019)]

This is an important consideration for women moving through their menopause transition, especially those women who may already be overweight going into peri-menopause. It’s a vulnerable time for their metabolic health, especially if they aren’t sleeping.

Metabolic health impacts every bodily system and is predictive of many chronic diseases (Marsh et al, 2023).

To me however, there is so much emphasis on increased high-intensity metabolic workouts (such as Crossfit), but many women in midlife haven’t got the time, energy, motivation or joint health to undertake these workouts, simply because they aren’t sleeping and changing hormone levels can contribute to low moods and depression.

As such, we need to also look at their diet (increasing adiponectin levels), their movement capability so that they can progressively undertake enough aerobic exercise to stimulate mitochondrial improvement, and of course, improve their sleep, liver and gut health.

All of these factors are important in order for us to succeed as Menopause Weight Loss Practitioners and as Health Practitioners, thus helping our clients to enjoy a healthier life as they move into their post-menopause years.

References:

Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017 Jun;13(4):851-863.

Izadi V, Azadbakht L. Specific dietary patterns and concentrations of adiponectin. J Res Med Sci. 2015 Feb;20(2):178-84.

Jiménez-Sánchez A, Martínez-Ortega AJ, Remón-Ruiz PJ, Piñar-Gutiérrez A, Pereira-Cunill JL, García-Luna PP. Therapeutic Properties and Use of Extra Virgin Olive Oil in Clinical Nutrition: A Narrative Review and Literature Update. Nutrients. 2022 Mar 31;14(7):1440.

Marsh ML, Oliveira MN, Vieira-Potter VJ. Adipocyte Metabolism and Health after the Menopause: The Role of Exercise. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 14;15(2):444.

Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, Squadrito F, Altavilla D, Bitto A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017:8416763. ,

Sanchis, P., Calvo, P., Pujol, A. et al. Daily phytate intake increases adiponectin levels among patients with diabetes type 2: a randomized crossover trial. Nutr. Diabetes 13, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-023-00231-9

Steiner BM, Berry DC. The Regulation of Adipose Tissue Health by Estrogens. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 May 26;13:889923.