‘Menopause is usually a cause of many concerns’, mentions the 2017 report on obesity in menopause (Kozakowski et al, 2017), ‘and one of the most important, is the fear of weight gain’.

Overweight and obesity, according to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO) are considered as an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health (WHO, 2016). For those of us who have ‘been there’ with our increased fat distribution during our menopause transition, some of these health issues include:

- higher blood pressure

- changing cholesterol levels

- erratic blood sugar levels which can lead to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes

- aching ankles and muscles

- fluid retention

- and the issue that got me the most, an inability to tolerate exercise.

Like many women reaching their 40s and early 50s, my own weight gain arrived almost out of the blue. I was still exercising, eating healthily, but still I felt bloated and ‘heavy’, especially in my breasts. In comparison to hot flushes and insomnia, this was one of the most difficult changes in my body to comprehend.

The ageing of the global population calls for a better understanding of the age-specific metabolic changes which differ significantly by gender, mentions the authors of an extensive study exploring metabolic changes in menopause. (Auro, Joensuu et al, 2013).

New research also suggests that the menopausal transition period in ageing women is strongly associated with weight gain, which, in up to 70% of women, is now a known symptom of menopause (Kodoth et al, 2022).

Furthermore, emerging evidence shows that weight changes during menopause increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) and Metabolic Syndrome in postmenopausal women. [Abildgaard et al., 2021; Fenton, 2021; Samar, et al, 2022; Se Hee Min et al, 2022].

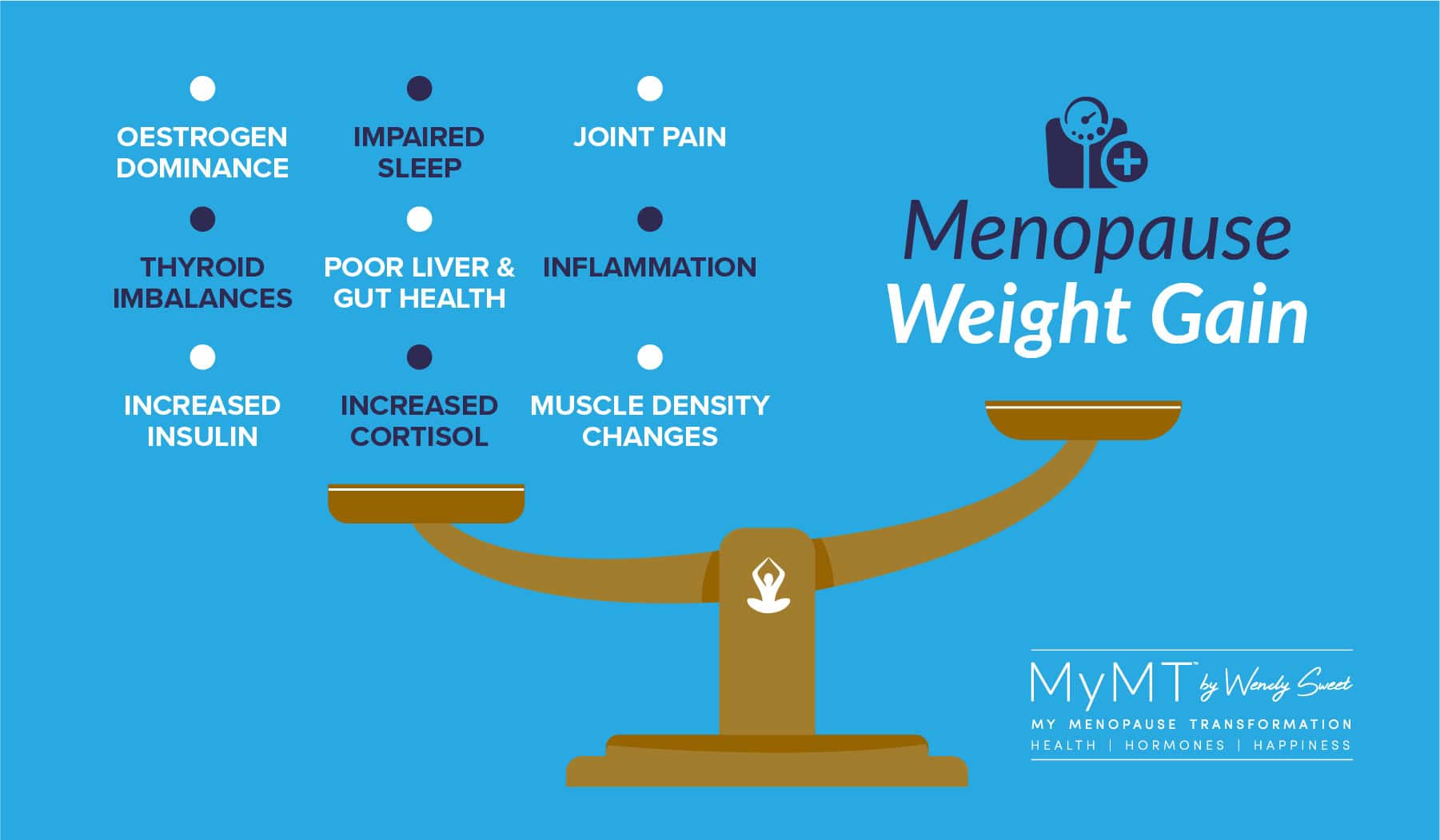

Factors that may contribute to these changes include our normal ageing, hormonal factors, changes in diet, poor sleep patterns, poor gut health, fatty liver disease, and reduced physical activity. Many of these factors are talked about in my coaching group by women on the MyMT™ programmes, so I’m not surprised that evidence is confirming these as contributing factors to menopause weight gain and obesity.

What I didn’t realise at the time of my own weight gain (and mainly breast and belly fat gain) was that the more abdominal and diaphragmatic fat that accumulated, the more that my fat cells were expanding. Much of this expansion was possibly due to oestrogen storage. I had no idea that fat cells generate their own local production of oestrogen and are now recognized as an important endocrine (hormonal) organ releasing an abundance of inflammatory markers. Did you? (Mair et al, 2020).

Oestrogens in women are responsible for the accumulation of fat in subcutaneous tissue, particularly in the breast, gluteal and thigh regions and around the abdomen.

Prior to menopause, oestrogen receptors connect with circulating oestrogens to maintain our menstrual cycle and to keep us healthy for reproduction purposes.

During menopause (when our periods are altered as we progress towards the cessation of them with age), these oestrogen receptors also attract other steroid hormones – mainly androgens (testosterone and androstenedione).

Whilst these are typically known as male hormones, don’t let that fool you – if you still have your ovaries, you are also producing these androgens as you move into post-menopause. They are also produced in the adrenal pathway, when we are feeling stressed and can’t sleep. This occurs when cortisol, our chronic stress hormone, is high throughout the day.

But here’s the other issue – if you are overweight or obese going into your menopause transition, this has an impact on the conversion of these androgens to oestrogens. It’s a confusing time for your fat cells. Because your fat cells love storing excess oestrogens in your body.

Fat is metabolically active and oestrogen has a role to play in this. Our fat cells love to store oestrogen and because women have enzymes that make them store fat around their abdominal region – which is part of our ancient ‘survival’ physiology – mid-life is a time of our lives, when we become more vulnerable to a condition called oestrogen dominance.

I explain this in more detail in my video below.

But fat-storage is not the only part of the menopause weight-gain story. Our liver health matters too.

If the liver is fatty or inflamed, it can’t clear excess oestrogens.

When our liver can’t metabolise excess oestrogens effectively, our fat cells store these additional oestrogenic compounds as we move through menopause.

Hence, oestrogen becomes the ‘dominant’ hormone in relation to it’s opposing hormone, progesterone. This makes us ‘oestrogen dominant’ and as a consequence of this, progesterone levels can become low. Your hot flushes, bloating, water retention, sleep, sore joints and aches and pains may become worse.

What happens then, is what happens to millions of women around the world in menopause – including myself. Progesterone becomes too low in contrast to oestrogen, so we feel bloated, heavy, sore and uncomfortable. It’s exhausting carrying all that excess weight around too.

Breast tissue has numerous oestrogen receptors, so they can become swollen, heavy and uncomfortable. For those of us who enjoy exercise, heavy breasts and increasing belly-fat, make exercise that much harder to tolerate. Don’t even mention the expense with having to purchase new bras!

As well, abdominal obesity is a key factor in the development of Insulin Resistance (my article on this is HERE) and a condition called Metabolic Syndrome. This is a cocktail of health issues (high blood pressure, high cholesterol, high blood sugar and high triglycerides and for many of you, fatty liver) that arises from being overweight or obese in menopause.

When we store excess oestrogens in our fat cells (including liver and breast tissue) then we can develop a condition called oestrogen dominance. What this means is that oestrogen becomes the ‘dominant’ hormone to the detriment of progesterone as we move through menopause and into post-menopause.

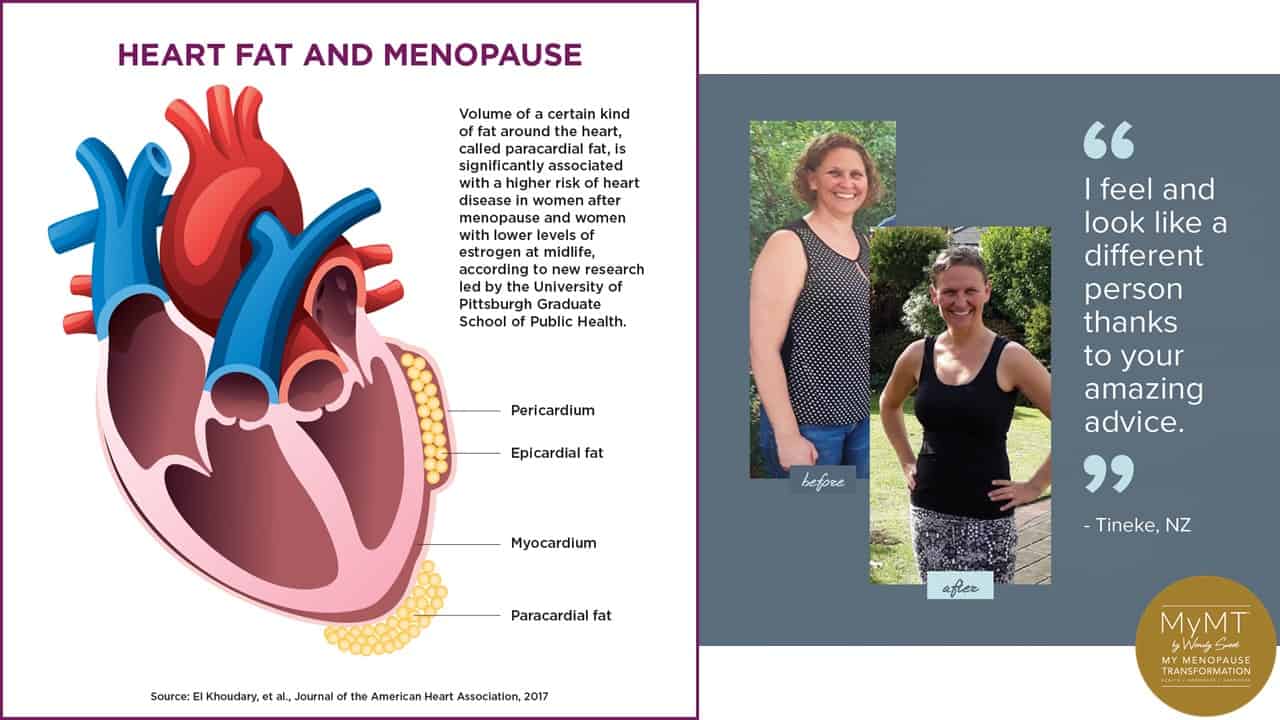

However, it’s not just the fat cells in the abdominal area expanding with excess oestrogen – fat cells may be expanding around the heart muscle as well. This is known as para-cardial fat and this type of fat increases our risk for heart disease as we age. Furthermore, the layer of para-cardial fat increases the stress on our heart, especially if we aren’t sleeping. It’s a double-whammy of health chaos as we get older and it’s important to turn this around.

As I slowly pieced together the menopause-misery jigsaw, I pulled together cardio-vascular research, diabetes and heart-health research as well as physical activity and longevity studies and of course nutrition research that was focused on mid-life women’s health and weight management.

When we aren’t sleeping, when our joints feel sore and we are losing precious muscle and becoming oestrogen dominant, then our metabolism changes too. It’s why I loved this insight from research out of the Australian National University, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

If I had this research a few years ago, it would have saved a lot of lonely research of my own. In a review of studies that included more than 1 million pre- and post-menopausal women, the researchers learnt what I and many other women, have discovered in real life – that our waist circumference increases during and after menopause and as such, there is a shift in our metabolism, which can send us into worsening health with age.

“It’s important to understand how women’s bodies change as they age because women have higher rates of some diseases than men”, said Ananthan Ambikairajah, a PhD candidate at the Australian National University, who led the study.

“The implications are important, because central fat has been linked with dementia risk, and central fat is linked with cardiovascular disease risk. As such, more attention needs to be paid to central fat accumulation, because that’s the bad stuff,” mentioned Ambikairajah.

Every extra kilo of weight is an added burden on your joints, heart, liver, cholesterol, muscle function and insulin levels as you age. That’s what concerns numerous women on my 12 week Transform Me programme as well. When you apply the promo code JANUARY24 this gives you my best savings for 2024 – I hope you can join me.

References:

Abildgaard J, Ploug T, Al-Saoudi E, Wagner T, Thomsen C, Ewertsen C, Bzorek M, Pedersen BK, Pedersen AT, Lindegaard B. Changes in abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue phenotype following menopause is associated with increased visceral fat mass. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 20;11(1):14750.

S. R. Davis, C. Castelo-Branco, P. Chedraui, M. A. Lumsden, R. E. Nappi, D. Shah, P. Villaseca & as the Writing Group of the International Menopause Society for World Menopause Day 2012 (2012). Understanding weight gain at menopause, Climacteric, 15:5, 419-429.

Fenton A. Weight, Shape, and Body Composition Changes at Menopause. J Midlife Health. 2021 Jul-Sep;12(3):187-192. doi: 0.4103/jmh.jmh_123_21.

Egger, G. & Dixon, J. (2009). Inflammatory effects of nutritional stimuli: Further support for the need for a big picture approach to tackling obesity and chronic disease. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 11, 137-49.

Kozakowski, J., Gietka-Czernel, M., Leszczyńska, D., & Majos, A. (2017). Obesity in menopause – our negligence or an unfortunate inevitability?. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review, 16(2), 61–65.

Mair KM, Gaw R, MacLean MR. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction – implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020 Sep 18;10(3):2045894020952019.

Manco, M. ,Nolfe, G. , Calvani, M., Natali, A., Nolan, J., Ferrannini, E., Mingrone, G. (2006). Menopause, insulin resistance and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Menopause, 13 (5), 809-817

Nelson LR, Bulun SE. Estrogen production and action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 Sep;45(3 Suppl):S116-24.

Patni, R., & Mahajan, A. (2018). The metabolic syndrome and menopause. Journal of Mid-life Health, 9(3), 111–112.

Samar R., El Khoudary, Alexis Nasr. Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Does Menopause Matter?, Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research, 2022, 100419, ISSN 2451-9650.

Varghese M, Griffin C, McKernan K, Eter L, Abrishami S, Singer K. Female adipose tissue has improved adaptability and metabolic health compared to males in aged obesity. Aging (Albany NY). 2020 Jan 26;12(2):1725-1746. doi: 10.18632/aging.102709.

Weickert M. O. (2012). Nutritional modulation of insulin resistance. Scientifica, 2012, 424780.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheets (2020). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight